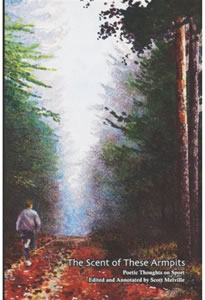

The

Scent of These Armpits: Poetic Thoughts

on Sport

Publisher:

BookSurge Publishing

Pub. Date:

December 14, 2007

ISBN-10:

1419678736

ISBN-13:

978-1419678738

Edition

Description: paperback,

304 pages

Reviewer: Joseph Powell,

Professor, English, Central Washington

University

I must admit that I was immediately attracted

to Scott Melville's anthology by the title.

It suggested a rather unsentimental compilation

of poems and writing about the sweaty

business of sport. He takes his title

from Walt

Whitman, that poet of lived life in

its full sweep of triumph, sensuality,

failure, contradictions, and generosity.

Melville has a kind of Whitmanesque apprehension

of sport that runs from a mawkish, unapologetic

endorsement to wry, hard-headed examinations

of its complexities and difficulties.

Both the way he has organized his material

and wide ranging examples speak to his

abiding love of sports.

The chapters are divided into poems about

the joys of sport, the drama of it, the

various skills required, philosophizing

about it, aging and death in sport, and

wellness. Each of these chapters has twenty

to forty entries, and every entry has

a brief biographical note about the author.

These authors range from the most obscure

to the most famous writers in English.

For example, there is a poem by John

Gillespie Magee, Jr. who died in WWII

on a bombing mission, but sent home a

poem about flying three months before

he died, and there are poems by Vigil,

Wordsworth, Dickinson, Shakespeare, and

Yeats. Yet there is also a fair and just

sampling of fine contemporary American

poets who would be obscure to most Americans,

but famous among poets: writers like C.

K. Williams, Robert Francis, Linda Pastan,

Donald Hall, Maxine Kumin, Peter Meinke,

A. R. Ammons, Stephen Dunn, Gwendolyn

Brooks, etc.

This project was clearly a labor of love

that must have consumed thousands of hours

of reading and research and note-taking

and categorizing. The breadth and inclusiveness

of material are matched by the inclusiveness

of sporting activity. In the Preface,

Melville says "I am broadly defining

sport to encompass young and old, male

and female, as they engage in and reflect

upon their diverse athletic endeavors."

Besides the predictable array of sports,

he includes almost any activity that requires

some physical output and may have an aesthetic

attraction to participants like canoeing,

dancing, fishing, juggling, skateboarding,

sledding, stationary bicycling, and walking.

His aesthetic principle for choosing pieces

was that "all selections avoid obscurity

and ring with a beautiful clarity."

He certainly delivers on this promise.

Even the poems and scraps of prose that

seem to be conventional in sentiment usually

have redeeming descriptions of the activities

they describe which make the reading worthwhile.

Although these descriptions are often

charming, my favorite section in the book

is "Philosophizing About Sports,"

which looks at the underside of human

endeavor and tries to make sense of it

on the deepest levels. For example, in

Pat Conroy's piece called "My Losing

Season," he says "Winning is

wonderful in every aspect, but the darker

music of loss resonates on deeper, richer

planes. . .Winning makes you think you'll

always get the girl, land the job, deposit

the million-dollar check, win the promotion,

and you grow accustomed to a life of answered

prayers. Winning shapes the soul of bad

movies and novels and lives. It is the

subject of thousands of insufferably bad

books and is often a sworn enemy of art.

Loss is a fiercer, more uncompromising

teacher, coldhearted but clear-eyed in

its understanding that life is more dilemma

than game, and more trials than free pass"

(118).

In a culture whose predominate values

center on success, fame, and victory,

we need these reminders that loss is a

better teacher, that emotional drive is

complicated ("See

the son of grief at cricket/ Trying to

be glad") (128), that "excellence

is millimeters not miles" (112),

that pain has its value. Ronald Wallace

wrote a poem about a Miss Bricka who lost

in a semi-final round in a Pennsylvania

tennis tournament in which he says, "Bluely,

loss/ hurts in your eyes—not loss

merely, / but seeing how everything is

less/ that seemed so much, how life moves

on/ past either defeat or victory/ how,

too old to cry, you shall find steps to

turn away" (145). It is reading poems

and prose like this that helps us find

the steps to turn away with some dignity,

some resolve, some lessons learned.

However, this book essentially celebrates

motion, the joys of physicality unperfumed.

It is a marvelous tribute to activity,

our bodies in the act of striving, taking

full pleasure in being alive no matter

how old we are.

|